Between memory, archives and artificial intelligence, Russian artist Alexey Yurenev transforms the absence inherited from his war veteran grandfather into a study of the representation of horror and the power of images to construct and distort history. His work Silent Hero will be on display at Prompting the Real, on 15 and 16 November 2025 at the Palazzo Poggi Museum (Bologna).

Born in Moscow and now working in documentary photography and visual research, Alexey Yurenev has transformed an incomplete family legacy, the medals of his war hero grandfather, into an artistic investigation of memory, absence and the role of images in the construction of history. In Silent Hero (2019–ongoing), the artist intertwines archives, family albums, interviews with Red Army veterans and emerging imaging technologies across three different formats. In the artist’s book Seeing Against Seeing, he reinterprets War Against War! by anti-militarist Ernst Friedrich a century later, bringing together documentary images from the First World War with those generated by AI trained on photographs from the Second World War. In the film No One is Forgotten, he brings these synthetic images back to Red Army veterans, transforming them into tools of collective memory where images reactivate the past. Finally, in the diptych FACE/OFF, he relates the silent landscapes of battlefields to the surgical reconstruction of a contemporary soldier’s face, reflecting on his own perception of horror through the camera. Together, these chapters compose a ‘multivocal and multimodal’ methodology that uses technology to reopen questions rather than close them. What, then, can art reveal in an age when photography and digital images oscillate between document, fiction and simulation? Can artificial intelligence become a tool for historical investigation, capable of bringing back repressed memories and traumas? Ahead of PROMPTING THE REAL – Artists AI co-creation, a two-day exhibition, talk and performance event to be held on 15 and 16 November 2025 at the Palazzo Poggi Museum, Via Zamboni 33, Bologna, we asked Alexey Yurenev.

Alexey Yurenev is an artist, visual researcher and educator. His work explores the intersections between memory, technology and knowledge production. He teaches in the MFA programme in visual arts at Columbia University and is a faculty member at the International Centre of Photography (ICP) in New York. His work has been exhibited internationally at institutions such as FOAM (Amsterdam), Hangar (Brussels), MOMus Modern/Costakis Collection (Thessaloniki) and the Rencontres d’Arles. He is the author of the book Seeing Against Seeing (2025). He has received awards from Photographer of the Year International and the Silurian Society Award for excellence in cultural and artistic journalism. He has also been nominated for an Emmy Award and the FOAM Paul Huf Award. He is co-founder of FOTODEMIC, an online platform dedicated to innovative visual strategies, and founder and executive producer of Living Room, a monthly public programme for ICP alumni.

Find out moreVisit the official website

In your account, the origin of Silent Hero seems to be deeply intertwined with your family history and with the figure of your grandfather, a war veteran. How did his memory — or perhaps his absence — influence the birth of the project?

I grew up in Moscow in 1986, forty-one years after the end of the Second World War, but the narrative of the conflict was everywhere: in films, monuments, parades. Everyone had a relative who had fought; mine was my grandfather, Grigoriy Lipkin, who made it to Berlin, participated in the liberation of Auschwitz and was decorated as a hero. But he never spoke about his experiences. Whenever anyone asked him about it, he would cry or joke. In Russia, there is a saying: “True heroes are silent; those who speak invent or exaggerate”. If you had seen the trenches, you didn’t talk about it. Paradoxically, however, every year on my birthday, my grandfather told me that, as his only grandson, I was responsible for carrying on his memory and his medals. When he died, I received the medals, but not the memories. It was at that moment that I began to reflect simultaneously on absence and how it manifests itself within a narrative as enormous as that of the Second World War in Russia.

Looking at my family archive, which contains about fourteen images, I saw only my grandfather posing proudly, in the studio or in the field: a war entirely reconstructed. In state archives, such as that of the Russian Ministry of Defence, on the contrary, I found only triumphs and victories, images often staged or retouched. One was silent and “undercommunicated”,the other shouted and “overcommunicated”: both emptied the real experience of meaning. So, I asked myself how to arrive at an image that does not persuade with realism but reveals what the camera cannot show.

Is there a specific moment when this reflection on photography and absence meets Artificial Intelligence?

In 2019, I was working in Russia. During that time, I attended a lecture by an American theorist, Fred Richen. His lecture was on post-photography and the future of photography. Among the examples he showed was a project called This Person Doesn’t Exist: a website featuring a person’s face generated by artificial intelligence. For me, as a photographer, encountering an image that looked like a photograph but wasn’t challenged my practice. It raised two fundamental questions. The first one: what do I do, as a photographer, in a world where technology exists that can simulate my own language? The second one: how can I use this technology, often used for manipulation or deception, for something meaningful? At the time, I was working mainly as a documentary photographer, so I was concerned with presence: I photographed what was in front of me, faithful to the promise of photojournalism, which is to bring events, places and people that the public cannot see with their own eyes to the public. But my encounter with AI opened up a new perspective: the possibility of showing places and events that never existed but could have existed. When I looked at the images in This Person Doesn’t Exist, created by Philip Wang, I occasionally noticed imperfections: a hole in the ear, a burn, a spiral, a flaw. To me, these were not errors, but gaps in the imagination of non-human intelligence. There, I sensed the possibility of collaboration. My grandfather’s story became – a bit like a MacGuffin1, to quote Hitchcock – a pretext for investigating the real “silent heroes”: the images themselves.

How did you develop Seeing Against Seeing and what kind of images did you want to achieve?

It was during the Covid period: while many were learning to bake bread, I had to learn to program with Python and managed to create an AI based on a GAN system, a General Adversarial Neural Network2, which works not on text but on images and is a feedback learning system between generator and discriminator. At the time, there weren’t many systems available for generating war images: some were already pre-trained, but I didn’t want to use them because it was essential for me to design a tailor- made AI that only knew about the Second World War. Working on such a sensitive topic, I wanted to have control over the dataset. I found a public archive of the Second World War with 35,000 images3. GANs require millions of perfect data points, but my dataset was deliberately imperfect: I wasn’t looking for accuracy, but rather an image that evoked war rather than describing it, leaving room for the viewer. During training, instead of correcting deviations, I encouraged them, treating AI as a collaborator. Paradoxically, the results were more consistent with the theme of repressed memory.

In Seeing Against Seeing, these images are derived from portraits of soldiers — men like my grandfather — who, under certain parameters, are transformed by AI into ambiguous and disturbing figures, monsters. I discovered that AI, if left to its own devices, becomes something more: not just statistics, but psychology. It is as if it lifts the veil of photorealism and reveals what lies beneath the skin: a memory beneath the memory, the true face of war — grotesque, disturbing, human and inhuman at the same time. In this sense, I believe that artificial intelligence can become a tool for historical investigation, provided that we consider its limitations: it is not something that provides answers but rather generates new questions. In the film No One Has Forgotten, for example, I bring the generated images to veterans and use them as a starting point to reactivate their memory. I never say, «This is war, this is a soldier», because I don’t know It is they, the survivors, who give meaning to those visions, who remember things they had never said or seen before.

In your work, you seem to move constantly between historical research and artistic interpretation. How do you balance this tension and, in the process, do you feel more like an artist, researcher or archivist?

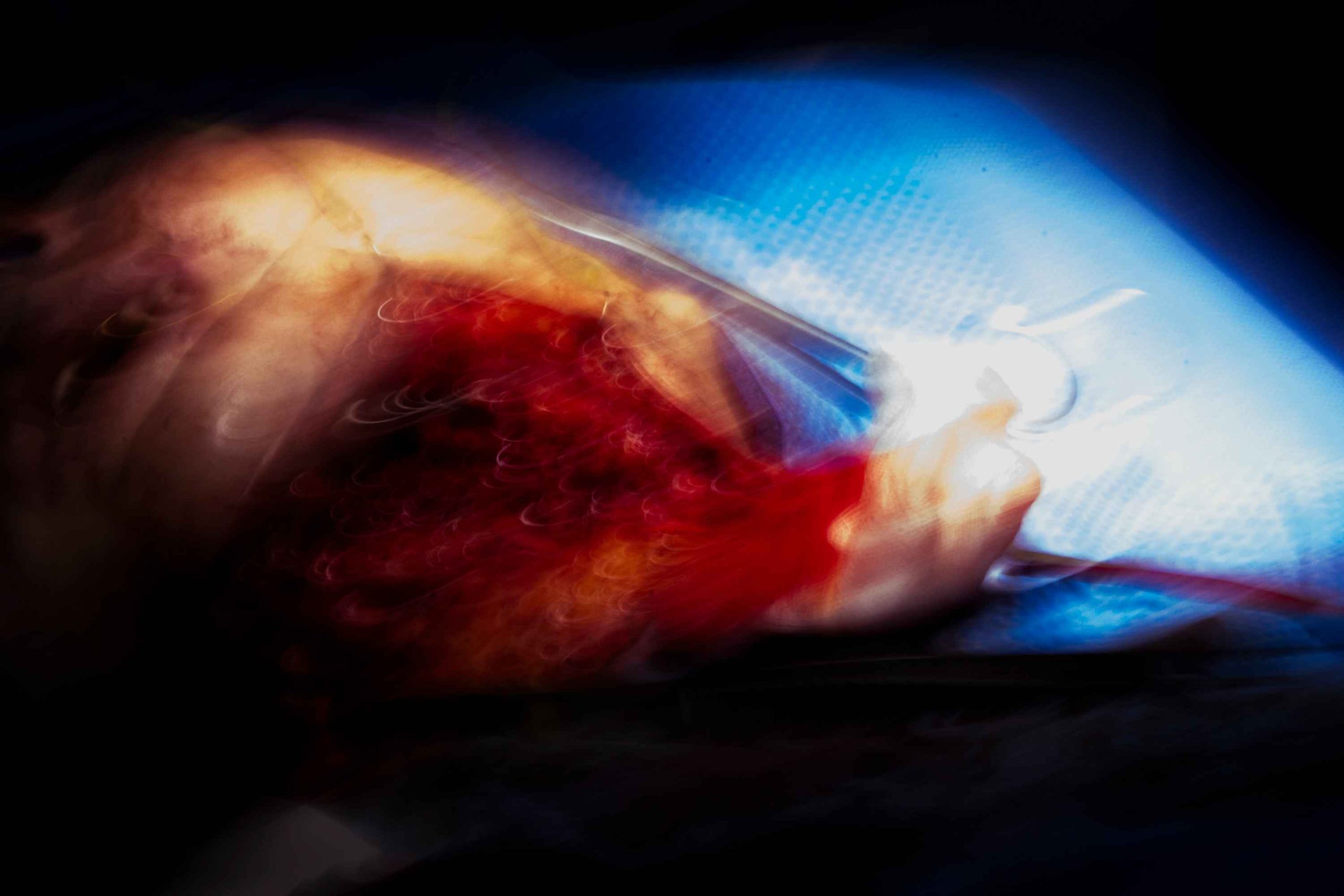

Silent Hero is a way to construct a multivocal and multimodal image of an event, freeing it from a single black-and-white perspective. At each stage of the project, I wear a different ‘hat’, but each one informs the other. The work on AI for Seeing Against Seeing, for example, transformed my photographic practice, prompting me to question the technological potential of the camera as a tool for revealing tacit knowledge. I am thinking of the surgical images of a Ukrainian soldier in FACE/OFF (II): there, I used the shutter speed to measure my own tolerance in looking at what was in front of me.

The longer I hold down the shutter, the longer I can hold my gaze – but the less sharp the image becomes. So the camera no longer measures only visible reality, but also my limit in seeing it. Similarly, when I photograph in the field, I use classic methods, such as a large- format 8×10 camera, but with orthographic film that does not record red, which is invisible to the human eye: it is a gesture to strip reality bare, remove a layer and get closer to the essence of the event. And then there is my work with veterans for No One is Forgotten, where I also become a griot, an oral storyteller: I collect and weave stories, collaborating with them as an artist and as the grandson of a veteran. In short, yes: I am an artist, researcher, photographer and storyteller all at once. My goal is to construct a choral narrative, made up of points of view that coexist, contradict and complement each other.

Do you think art can still play a role in revealing the “truth” – or multiple truths — especially in the perception of war? And, in this sense, against which rhetoric of war does your “unmasking” work?

I don’t believe in truth as something absolute or stable. I prefer to think of truth as a movement, a current that flows through the gaze of the observer. I want my work to invite people to explore different ways of seeing. “Truth” remains a dangerous word, but I believe that there are many truths, and that art, through its visual and narrative tools, can still give them form. That’s why, rather than working against something, I think I work for something: to challenge the idea of a fixed, linear, definitive historical narrative. I come from an experience in which I inherited the “post-memory” of war – an event I received without having experienced it. For years, I thought that images, photographs and history were solid grounds to walk on. But the reality, as recent events continue to demonstrate, is that that ground is not solid: it is liquid. My task, then, is not to look for solid ground, but to learn to swim so as not to drown. Similarly, when I think of those who enter the exhibition, my goal is to lift the veil of habituation. We live in a world saturated with violent images of war, but what do they really do to us? Do they bring us closer to the experience or distance us from it? Through a personal narrative that opens up to a broader reflection on visual culture, I invite viewers to ask themselves what it really means to “see war” and what images really do.

If your grandfather could have seen Silent Hero, what do you think he would have said?

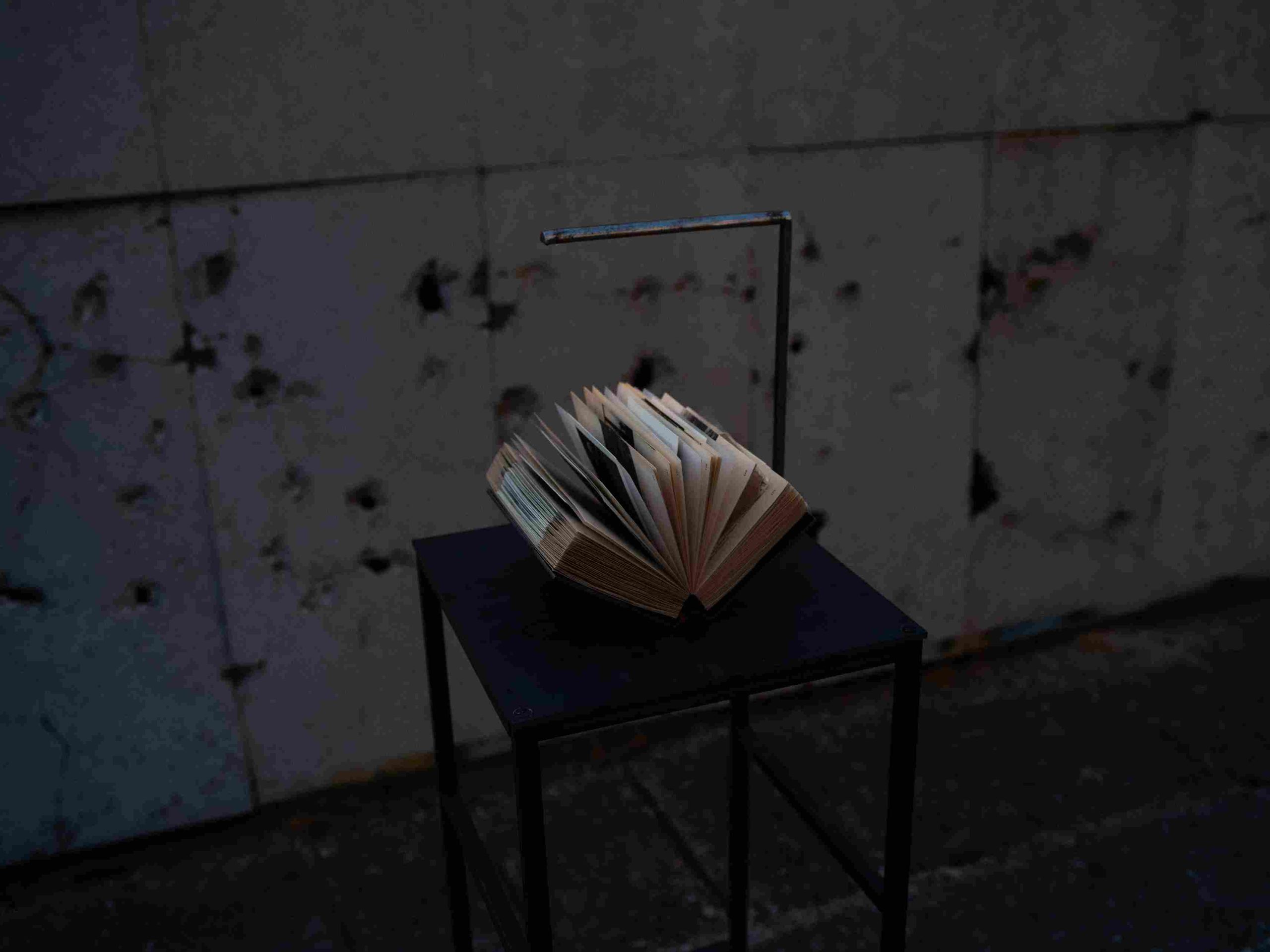

I would have to ask a medium to find out (laughs). I like to think he would have been proud, but I’m not sure. I can’t speak for the dead. However, I can recount an important episode. While researching how to train my AI, I discovered everything about him and found out the truth about his brother, who had been missing for eighty years: where and when he died, for example. When I finally had this information, none of those who could have shared its meaning were alive anymore – except my mother. It was a touching moment: I think I realised, in a way, my grandfather’s wish. But also in a strange way, because there was no one left to celebrate or mourn that discovery with. And so, another absence was created. I know nothing about his brother, except that he was ‘absent’. And his presence is defined by his absence. Even the images you see in FACE/OFF (I), those of the snowy landscape, represent that very emptiness: the attempt to confront something that cannot be filled. In that absence, I found the meaning of emptiness itself: emptiness is him.

- The term MacGuffin, coined by director Alfred Hitchcock, refers to a narrative device that drives the plot forward, but whose content is actually secondary: what matters is not the object or the search itself, but the journey it generates in the characters and the viewer. ↩︎

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are artificial intelligence models composed of two neural networks: a generator that creates synthetic data and a discriminator that attempts to distinguish it from real data. The two networks “compete” with each other, improving each other until they produce realistic results. GANs are used to create credible images, videos or texts, but they also pose ethical and technical challenges. Bassetti, N. (2024, May 22). GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks): cosa sono, applicazioni e vantaggi. Agenda Digitale. https://www.agendadigitale.eu/cultura-digitale/gan-generative-adversarial-networks-cosa-sono-applicazioni-e-vantaggi/? ↩︎

- The archive is available at waralbum.ru. It collects materials from all over the world: not only Russian, but also from the Allied and Axis forces: Japan, the United States, Germany, Italy, China, etc. ↩︎