How can art make complex connections tangible and activate a shared responsibility around the use of technology? Through AI War Cloud Database, a project of artistic research and an interactive installation, Sarah Ciston makes visible the connections between everyday digital technologies, Artificial Intelligence, and contemporary military apparatuses.

«More than 3 billion people in over 180 countries use WhatsApp to stay in touch with friends and family, anytime and anywhere», reads the website of the bright green app, founded in California in 2009 by Jan Koum and Brian Acton. A familiar and seemingly neutral digital infrastructure whose data have been used to train decision-making systems deployed in military operations, up to and including the selection and killing of people in the Gaza Strip. WhatsApp is not the only example of digital technologies that actively participate in contemporary violence and are entangled with military structures.

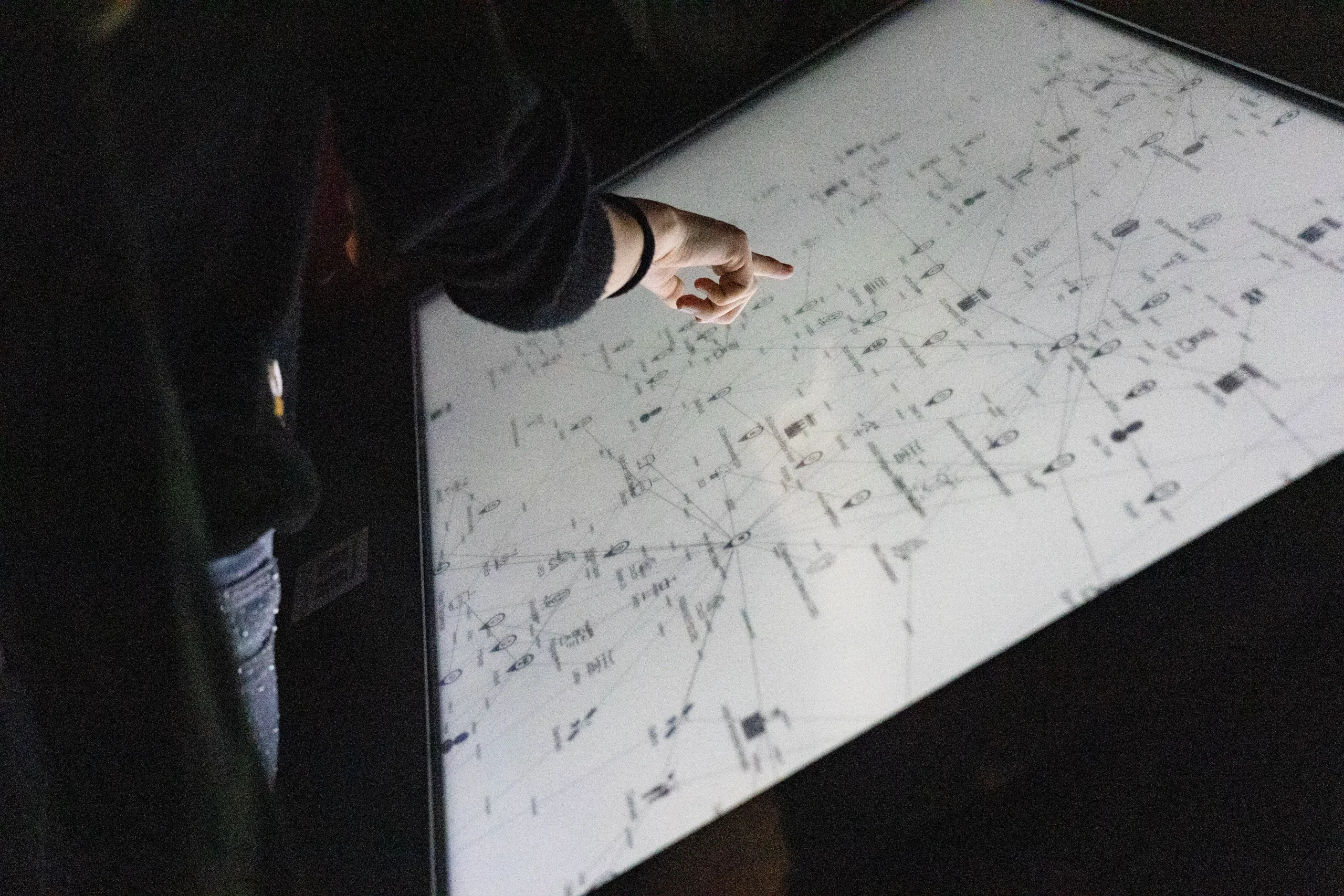

The short circuit that emerges between the intimate and the geopolitical—bringing our relationships and everyday lives closer to military structures and logics, such as the definition of military targets or the integration of algorithmic systems into surveillance—lies at the core of AI War Cloud Database. The project, an artistic research initiative and interactive installation, was presented in November 2025 in Bologna, in the military architecture hall of the Palazzo Poggi Museum, by the American artist Sarah Ciston as part of the exhibition Prompting the Real.

«I wanted to bring together, in a single tool, the connections between spheres that are usually considered distant but are in fact deeply intertwined, in order to ask myself—and others—what responsibility I, and we, have when using certain tools», Ciston explains.

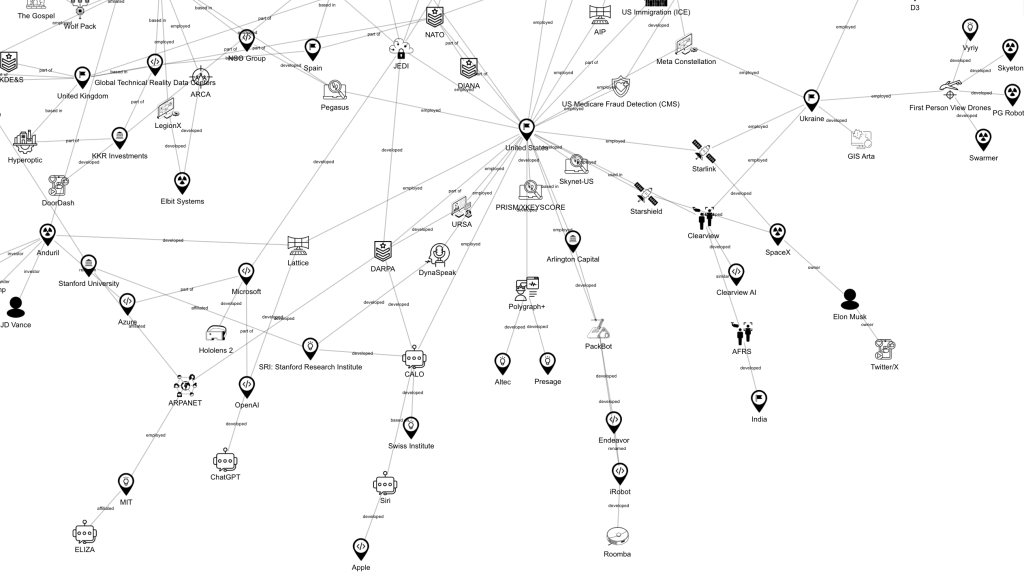

Unsurprisingly, the work takes the form of a large dynamic map: a network connecting technology companies, governments, Artificial Intelligence systems, commercial applications, and military tools. This configuration is an open political question—one that offers no reassuring answers but instead forces those who engage with it to confront what normally remains invisible.

Sarah Ciston is an artist-researcher who develops tools to bring intersectional and critical-creative approaches to machine learning. “AI War Cloud Database” won the 2025 S+T+ARTS Grand Prize at Ars Electronica. Ciston has received research fellowships from the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, the Center for Advanced Internet Studies, and the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society. Ciston is the author of “A Critical Field Guide for Working with Machine Learning Datasets” and a co-author of “Inventing ELIZA: How the First Chatbot Shaped the Future of AI” (MIT Press, 2026).

Learn moreGo to the official website

Making the invisible visible

The origin of the project, Ciston explains, lies in a convergence of moments and connections. «On the one hand, I saw AI increasingly used in military contexts; on the other, there was enormous hype around AI in art and commerce, and these two aspects almost never overlapped in the conversations around me», Ciston says. The technologies that recommend a film on a streaming platform and those that identify a “target” often share the same technical foundations: supervised machine learning, neural networks, classification, and prediction. In some cases, they also share datasets, cloud infrastructures, and developer companies. Contemporary conflicts, from Ukraine to Gaza, have become privileged sites for the development and testing of Artificial Intelligence systems, both for the states involved and for large technology companies, which view these contexts as opportunities for large-scale experimentation.

Within this framework, «discovering that WhatsApp data had been used to train targeting systems was one of the most powerful moments that pushed me to continue the project», Ciston recalls, because «it’s something I use myself, and it suddenly felt very close».

To build AI War Cloud Database, the artist carried out meticulous process of collecting, verifying, and interrelating materials that were already publicly available. The main challenge was to systematise fragmented information, engaging with the work of other researchers, independent investigative journalists, platforms such as Tech Inquiry1, and non-profits like Airwars2. Alongside these sources, Ciston also drew investigations by more mainstream media outlets and an in-depth review of a wide body of academic literature, in order to cross different perspectives and avoid partial or unbalanced interpretations. «I tried to look at a wide variety of sources and viewpoints in order to build a more accurate dataset», Ciston explains. A central role in the research was also played by materials produced directly by corporations and governmental institutions. «By examining corporate websites — by looking at what companies say about themselves — you can discover a great deal, as well as through public tenders or government contracts, which help clarify what governments claim to use, who they are paying, how much, and when».

The methodological choice to rely on publicly available data carries a profound political value. On the one hand, it shows how normalised and legally transparent the infrastructures of technological warfare have become; on the other, it asserts the possibility of democratising access to knowledge by bringing this mapping together into a single database, «readable even in a spreadsheet, to lower the barrier to entry», Ciston explains. The project’s mapping is, and will remain, open source, as an invitation to collaboration and collective awareness.

When research becomes art

AI War Cloud Database could be understood as a journalistic investigation or as an effective dissemination of an academic publication; in reality, however, it represents a very precise epistemological position: artistic thinking as a guide for the processes of collecting and producing knowledge. It is a form of thinking that makes it possible to experiment with materials and ideas in ways that cannot be reduced to demonstration or linear argumentation, and that accepts that reality contains structures that cannot be understood solely through discourse or raw data. These structures instead require form, environment, temporal mode of engagement, and the involvement of the body.

Ciston reiterates this position clearly: «My work can be framed as artistic research, combining critical work and artwork. Where journalism tends to operate through revelation and attribution — “who did what and when”— art can ask, “what does this mean for me?” Art enables a different form of experimentation, one that emerges from an embodied dimension, works with materials in a different way, and opens up another possibility for imagination: that of modeling the world not only as it is, but also as we might wish it to be or perceive it to be. Once these models exist — whether they serve to imagine how the world could be or to make visible what was previously unseen — it becomes possible to test them, to deepen them, and even to bring them back into other domains. For this reason, I believe that today there is an opportunity — and perhaps also an urgency — for art to push beyond its customary boundaries».

In the AI War Cloud Database model, visitors can grasp the force-directed graph—the tangled graph that dynamically reconfigures itself—move nodes, and bring new connections to the surface between applications, states, institutions, and companies. In this way, the possibility of “moving” the map produces an inversion: it is no longer only technology that unconsciously directs our gestures, but we who, consciously and at least for a moment, intervene in the visible form of the connections.

During the days of the exhibition, the artist observed that many people intuitively understood the operation at work in AI War Cloud Database: they began to draw their own connections and to look for nodes that touched their own lives. «It was really nice to be able to talk directly with the audience. When I presented the work, I had the chance to engage with people and was happy to discover that the piece was clear and engaging for individuals of different ages and from different places. Some people even asked me directly, “So which apps should I use instead?” “Which tools would you recommend?” And for me, that was fantastic. I secretly hoped that people would start asking themselves these kinds of questions, without me having to suggest the idea».

Which question for which future?

If there is one thing Sarah Ciston consistently rejects, it is the promise of a “solution” offered through interaction with the installation. In this refusal, the artist recognises an intrinsic ambiguity in what we call technological progress: every advancement opens up new capacities and new asymmetries; every “useful” tool can also function as a tool of control, just as every optimisation can become an acceleration of violence. Within this ambiguity, the most honest question is not “what should we do,” but rather “which questions must we learn to ask?”. The question of “what to use instead,” in fact, risks reducing the issue to a form of individual ethical consumption, when the use of any given technological tool inevitably ties us—as AI War Cloud Database makes clear — to other human beings.

When asked, «What do you think is the most urgent question we should ask when choosing to use or build intelligent tools?», Ciston responds unsurprisingly:

«Designers should always think about the human stakes and the potential impact of what they are building, and ask who is not included in the design process».

For those who use these tools, the artist instead proposes formulating questions grounded in an ethics of situated choice—one based on constant attentiveness and, above all, a willingness to be changed by what one has seen. «It’s very difficult to go all or nothing: in my own choices, I try to be as conscious as possible, but it doesn’t help to be too hard on myself. It’s not that I will never use one of the major global search engines or a generative AI, but I try to make informed choices about how much, how, and why I use them».

And if talking about the future always risks slipping into utopia or dystopia, the artist’s vision of the future brings us back down to earth. «I hope that in twenty years we’ll be having a different conversation—not about AI—and that we will have figured out how to be more connected to one another. And I hope that my students are making truly interesting work that speaks about what is happening in the world, and that I’ve somehow helped make that possible».

- Tech Inquiry is a small nonprofit which maps out relationships between companies, nonprofits, and governments to better contextualize and investigate corporate influence. https://techinquiry.org/ ↩︎

- Airwars is a not-for-profit transparency watchdog which tracks, assesses, archives and investigates civilian harm claims in conflict-affected nations. Founded in 2014 we are today a leading authority on conflict violence as it affects civilian communities. https://airwars.org/ ↩︎