Between language, fossils and artificial intelligence, Jerry Galle practises a reverse archaeology: he does not excavate the past but deposits signs and materials in the present so that a future intelligence might read them. In AI Messages, an AI creates a form of writing intended for itself; in Deeptime, the “technological fossils” imagine tomorrow’s geological archive. It is a journey into deep time that shifts the human away from the centre and asks what will remain of us. The two works are part of the exhibition Prompting the Real, which has just concluded at the Palazzo Poggi Museum in Bologna.

What does it mean to create something for a “future intelligence”? What traces of ourselves, as humans, will remain? And above all: what kind of history will emerge from what we leave behind today, whether deliberately or by mistake? The works of Belgian artist Jerry Galle, AI Messages and Deeptime, arise from this constellation of questions and from a gesture of temporal reversal: instead of “digging” to bring the past to light, he deliberately deposits material in the present so that a distant, perhaps post-human future might read and interpret it.

Jerry Galle, a fellow at V2_, conducts artistic research at the KASK School of Arts, University College Ghent. He investigates the complex and often unsettling relationship between digital technology, nature and culture, using software and digital images in unconventional ways and highlighting the pervasive role of technology in everyday life, the natural world and artistic creation. His work has been exhibited at Muhka, Bozar, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, the British Film Institute, Wiels, the International Film Festival Rotterdam, EMAF, the International Film Festival Hamburg, Museum Dr Guislain and Ars Electronica, among others.

Learn moreVisit the official web page

Galle explicitly speaks of «wanting to remove artistic work from contemporary noise» and of looking at it «as if we were seeing it in two thousand years», in a deep time, that is, on a geological timescale that exceeds human life by several orders of magnitude. Only then it is possible to establish enough distance to deactivate the anxieties and automatisms of the present and restore the imagination’s critical and generative function.

The two works were displayed for PROMPTING THE REAL – Artists AI co-creation (15–16 November 2025) at the Palazzo Poggi Museum (Via Zamboni 33, Bologna): two ways of preserving something of ourselves beyond the expiry of the present and observing who we are from another vantage point.

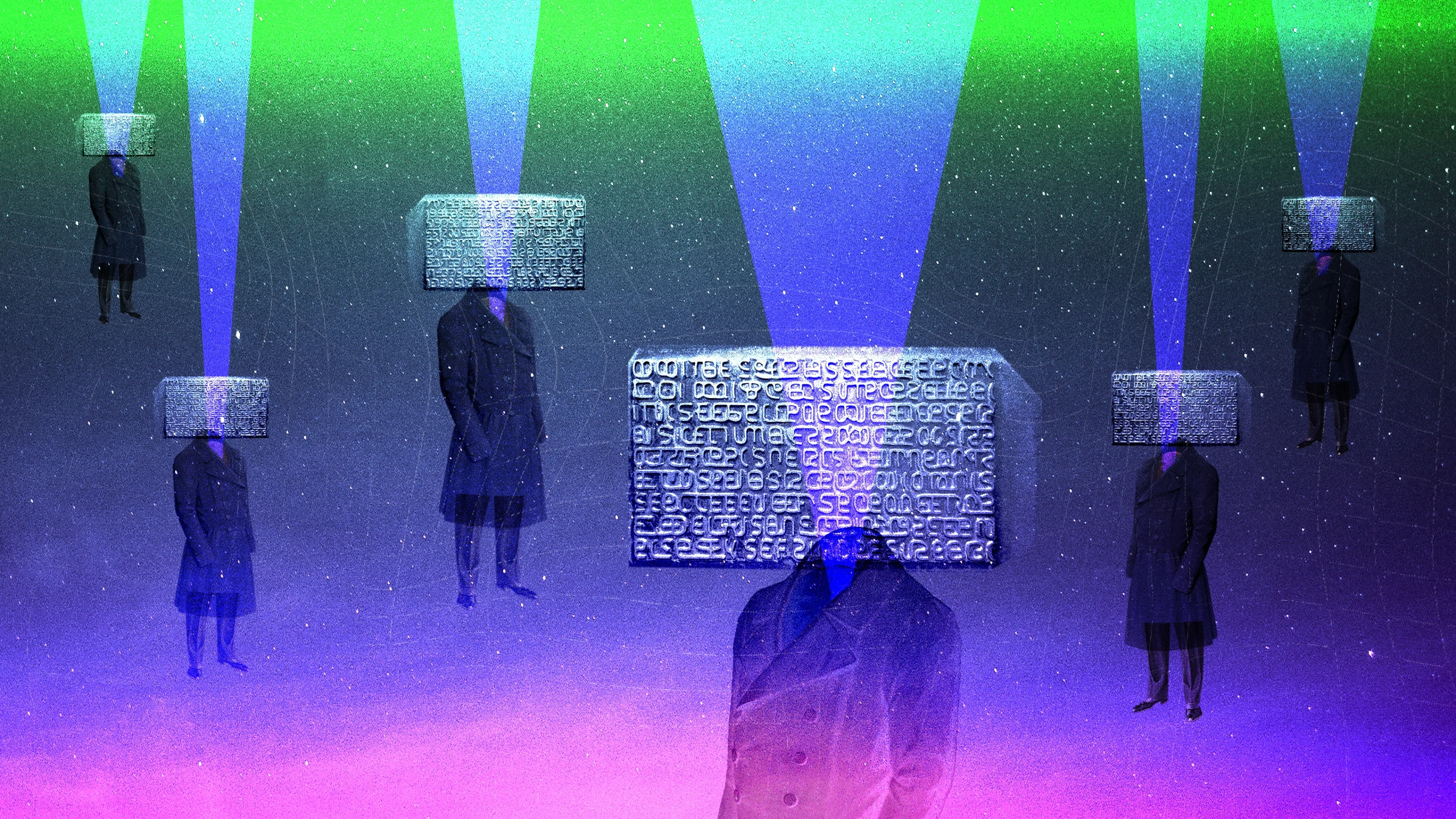

AI Messages, between language, encryption and aluminium

AI Messages began with an intuition: to consider language as «one of the first technologies» and to treat it as a device capable of enduring through time. «I was watching the documentary The Evolution of Technology: A Journey with Jim Al-Khalili1», Galle recalls, «and there was a line that struck me: language is capable of making ideas last. It’s simple, but it sparked something in me», enough to imagine a language not devised for us, but for a machine of the future.

«I thought: it might be interesting to have an Artificial Intelligence compose its own writing, so that in the future it would be readable only by itself».

The idea behind this gesture is twofold: to emancipate language from human control and, simultaneously, to build an archive for a non-human reader. In other words, to turn writing into an “untimely” deposit that eludes us today but may be deciphered by another intelligence tomorrow.

To create this alphabet, Galle turned to palaeography: he searched for and collected as many linguistic bases as possible. «Ancient and archaic, cuneiform and so on», he explains «in the form of fonts and vectors», often taken from public digital archives2, and used them to train a neural network capable of generating a new system of signs. Sound datasets were also integrated to recall that chapter of language history3 in which «the real revolution took place, when signs began to correspond to sounds». The training phase was relatively quick, but debugging — i.e. the phase in which system errors are identified and corrected until the output meets the desired criteria — took months, as the first outputs «were abstract, barely legible signs», and above all because the round-trip process — writing and then deciphering — repeatedly failed. «If I asked it to generate a simple sentence, like “I want to go for a walk”, the decryption would yield perhaps one or two words, never the full sentence. I had to build a second AI to decrypt the first and make them work together. Essentially, an encryption–decryption system».

Galle chose not to show the translations in the exhibition: «It would be too direct. I need time and imagination. I like to think that in a thousand years an AI might look at this language and laugh because it finds it silly, or, conversely, finds it profound. That possibility must be protected, including through the material itself», which becomes its guarantor. «I chose to inscribe the new code on aluminium because it endures. I also thought about Persian tablets and the idea of burying them so that someone might discover them one day. It was essential, for me, that the object could be preserved against digital oblivion».

Deeptime, between history, evolution and fossils

If AI Messages imagines preserving the present for the future through writing, Deeptime envisions preservation through mineralisation. The questions Galle asked himself while creating it are straightforward: what will enter the fossil record of the future? Will there be “technological fossils” from the Anthropocene? What form will a trace of plastic, silicon or copper take in a hundred thousand years, in deep time?

«I began reading about evolution and was struck by the idea, taken up by the biologist Lynn Margulis4, that alongside Darwinian evolution there is symbiotic evolution, and that the history of life is not an arrow but a web of attempts and failures, of re-emergences», Galle explains.

Life may have «evolved several times» and, just as many times, «de-evolved». In this light, technology becomes a sediment and a potential fossil that evolves and de-evolves with us.

To give form to this speculation, Galle first created a physical dataset before a digital one: he visited museums «in Brussels, northern France and the United Kingdom» to photograph samples and select specimens with «clear imprints that were not too “noisy”, otherwise the visual effect would be lost», he says. From this foundation, he trained an AI to imagine future fossils: a series of images that later became actual sculptures. «I liked the idea that the fossils were not made of plastic and that they could degrade», he explains. «So I used a 3D printer based on corn-derived compounds that are biodegradable», juxtaposing the promise of fossil durability with an awareness of the fragility of the medium — the same fragility inherent in our current silicon-based digital hardware.

Alongside the sculptures, Galle constructed a poetic taxonomy: a system of names, labels and brief descriptions that mimic scientific classification while simultaneously deviating from it, blending palaeontological vocabulary with invention. Its purpose is not to prove, but to orient the visitor’s imagination, like an index of possibilities. «The stories that people in the future will imagine do not need to be correct. Science requires evidence, but if everything must be proved, stories become constrained. I, on the contrary, want to open up possibilities». The goal is not a single interpretation, but narrative proliferation because «perhaps these fossils are only the beginning of a new story».

Just as AI Messages resists literal translation, Deeptime resists the closure of meaning. It is no coincidence, Galle notes, that some visitors have perceived the panels of AI Messages or the sculptures of Deeptime as traces of «an alien culture» or even «the origin of a cult»: reactions that confirm the generative function of this taxonomy, which serves more as a poetic guide than a manual.

Time as a form of freedom

Both AI Messages and Deeptime are speculative archives: one preserves languages, the other materials. Both reposition the human away from the centre and address an unknown observer, archiving, leaving clues, not representing but anticipating possibilities. Their eventual recipient might be a future AI, an ecosystem, a post-catastrophe community or a geologist of another species. It does not matter who: what matters is that someone might find these works and construct a story far into the future.

For Galle, time is not a neutral container but an active medium. «Time gives you freedom», he says. «It allows you not to be trapped by what is happening now», avoiding the obligation to take a stance within ethical and political categories that, although recognised, can be reductive for art; enabling works that are questions extended through time rather than immediate answers.

«I understand the criticisms and dangers of technology», Galle acknowledges, «but I needed, and still need, to look at it openly, without being constrained by the ethical urgencies of the moment».

To reach this position, Galle weaves art and science together without hierarchy, rooted in a longstanding fascination for natural philosophers such as Mary Anning or Friedlieb Runge, for whom «science and art were not separate». AI too is decentring. Galle insists on a concept of relational intelligence: «If you think about human intelligence, and perhaps the intelligence of all biological organisms, we depend on the environment and on interaction with others. Individual intelligence, on its own, is not that intelligent. You can ask me many things, but I would not know how to build a bicycle: that is why I need others and group intelligence». For the artist, this vision took shape in the age of the internet, «perhaps it even began with the internet», and today, with AI, «that dimension becomes even more compact and closer». The point, he concludes, is that «it is no longer just the individual: it is a network», and only within this network can we truly understand how we function. On the one hand, AI is «a sophisticated memory engine», he explains, a way of consolidating «all our data, thoughts, fears, hopes» into models that «memorise culture» and return it in predictive form. On the other hand, it is a material technology based on silicon and minerals of great fragility and ecological cost.

«It is fragile», Galle says, and for this reason we must seek other forms of computation, perhaps «more sustainable», in a horizon where deep time also becomes an ecological scale through which to assess what remains and what is lost.

- Learn more, Doc of the Day. (2025, January 30). The Evolution of Technology: A Journey with Jim Al-Khalili [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqXfvqIzpgs ↩︎

- Discover GitHub https://github.com/ ↩︎

- Further reading, Schmandt-Besserat, D. (2014). The evolution of writing. The University of Texas at Austin. https://sites.utexas.edu/dsb/tokens/the-evolution-of-writing/ ↩︎

- To better understand Lynn Margulis’ idea, University of California, Berkeley. (n.d.). Endosymbiosis: Lynn Margulis. Understanding Evolution. Retrieved [17/11/25], from https://evolution.berkeley.edu/the-history-of-evolutionary-thought/1900-to-present/endosymbiosis-lynn-margulis/ ↩︎