The project Mimosa Pudica by Valentina Vetturi unfolds in the dialogue between memory, technology and biology, offering an original reflection on digital accumulation and on the space between remembering and forgetting. Through a transdisciplinary practice that weaves together art, philosophy and science, the artist translates the biological behaviours of the plant into an operative metaphor for the digital world: a distributed, temporary and ecological form of memory.

In 1995, Jacques Derrida published Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, a text that today reads like an early diagnosis of our time. In those pages, Derrida identifies the act of archiving not as a neutral gesture, but as an expression of power and a will to dominate the past. Whoever guards memory defines its boundaries, deciding what remains and what is forgotten. That “archive fever”, the urge to preserve, classify and retain every fragment of experience, has become, in the digital era, a collective pathology. The infrastructure of global networks has transformed the archive from a delimited space into a continuous flow of data, and we ourselves have become unconscious archivists of our own lives. Within this tension between memory and oblivion, between permanence and dissolution, lies the work of Valentina Vetturi, who through Mimosa Pudica addresses a question both poetic and urgent: what can a plant teach us about the use of memory in the digital world? With Mimosa Pudica, Vetturi intertwines art, philosophy and science, where vegetal memory becomes both a mirror and an antidote to artificial memory. Two worlds that seem distant – those of carbon and silicon – come together in the archive.

Valentina Vetturi

Valentina Vetturi is a visual artist and researcher based in Bari, southern Italy. Her transdisciplinary and collaborative practice explores forms of digital ecologies and collective memories, unfolding through performance, text, sound, sculpture and new media. Her work originates from immersive experiences across diverse fields – from law to music, hacker culture to science – which she gradually translates into configurations in dialogue with space and audiences. In 2024 she won the Italian Council and collaborates with institutions such as the Lagos Biennale 2024, MAXXI Museum Rome and L’Aquila, Ma*GA Gallarate, and the Strauhof in Zurich. Vetturi teaches Video Installation and Multimedia Didactics at the Bari Academy of Fine Arts and Design for Painting at NABA in Rome.

Find out moreVisit her official web page

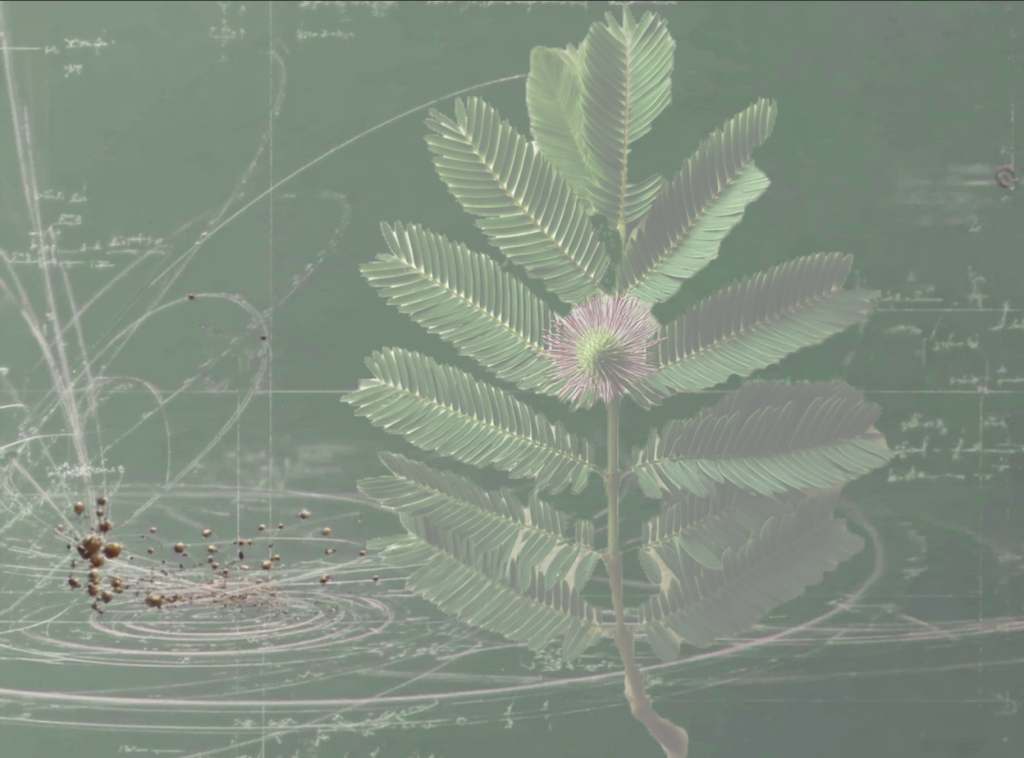

The plant as a guide for research

The sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica) reacts to the world through movements that are both language and relation, folding its finely feathered leaves in response to tactile stimuli. Today we know that the behaviour of this tropical herbaceous plant – native to South America and later spread to Asia, Africa and the Mediterranean basin – is based on a phenomenon known as “thigmonasty”: a rapid physiological response caused by variations in water pressure within the cells of the pulvini, small joints at the base of the leaflets. When the plant senses a vibration or a raindrop, the pulvini lose liquid, causing the leaves to fold. It appears to be an emotional gesture – hence the plant’s name – but in fact it is a sophisticated form of self-preservation.

This mechanism has been observed since the seventeenth century by scholars such as Descartes1 who referred to it when questioning the boundaries between matter and spirit, and later by Jagadish Chandra Bose2, an Indian physicist and botanist who conducted much of his research in plant physiology on the Mimosa pudica. In 2014, an article3 by ecologist Monica Gagliano added another chapter to this long scientific history, showing that the plant can “get used to” non-harmful stimuli, retaining the memory of the experience for weeks: a form of “brainless learning” through which plants can nonetheless learn.

«Reading Gagliano’s article, and discovering the ability of plants to learn and forget, was a turning point for the Mimosa Pudica research», says Vetturi.

«Although I am aware that the mnemonic capacity of the vegetal world is a controversial topic in science – some researchers, in fact, prefer to speak of habituation – that discovery was a turning point. I was struck by the idea that the plant could both learn and forget», says Vetturi. In her experiments, scientific practice becomes observation and performance, and the biological dimension of plant memory opens a new conceptual space for art, where knowledge does not stem from a centre but from a network of diffuse relations.

It was in this way that, in 2015, the artist sowed the seeds of Mimosa Pudica, supported by the Italian Council programme: a practice that, starting from a reflection on vegetal and digital memory, blends listening and research, intertwining philosophy, performance and science.

A theme – that of the interstice between remembering and forgetting – actually stems from more than ten years of research and works devoted to the digital, which had already led, in 2014, to the work Alzheimer Café: «a series of performances, sound installations and public interventions dedicated to “musical memories”, the last memories that poetically persist even when one no longer remembers one’s own name».

Cultivating knowledge: shared practices and open archives

There is no definitive version of Mimosa Pudica, because the artistic project is a process of research in constant transformation: more an ecosystem of practices than a single work. Like the plant that inspires it, the project moves and reacts, based on «forms of guided improvisation, where there is an initial score that changes in relation to the physical, social and symbolic context and to the audience – elements that transform over time».

Each stage of Mimosa Pudica, from MACTE in Termoli to MAXXI in Rome, represents a different phase in the growth of a large collective organism. Vetturi began by observing several mimosa plants in her studio in Bari every day, before inviting others – philosophers, historians of art and science – to grow and observe these plants and to take part in a series of round tables. They explored what are, in the end, the foundational questions of the project: «Can plants suggest a digital ecology that balances the enormous accumulation of data and information with the speed at which we forget?». And again: «How can we conduct such research without resorting to extractive methods, and by questioning our anthropocentric biases?».

The answers to these questions have not closed into results but opened into spaces for sharing. As Vetturi explains: «For me, artistic research is nothing more than an open form that develops through crossings and approximations. It evolves by sharing questions and doubts, rather than answers». In the proximity between species that the artistic practices of Mimosa Pudica manage to create – from performances to listening moments – the project’s initial intuition is revealed: «to challenge species differences, categories we take for granted».

«Someone once told me they could no longer look at plants the same way, or that when they walk their dog in a park, they feel as though the plants remember them», says Vetturi.

Unsurprisingly, Mimosa Pudica is increasingly becoming a space of encounter and contamination, where hierarchies between human and non-human dissolve. This is because the project does not anthropomorphise the plant, but adopts its point of view: slowness, responsiveness, distributed memory.

New perspectives on memory

In recent years, numerous studies have analysed the crisis of digital accumulation as one of the great paradoxes of our time. According to research by the Global DataSphere4, more than 350 exabytes of data are generated worldwide every day, a quantity expected to double by 2030. This vertiginous growth is not merely a technical issue: it has environmental, cognitive and cultural implications. Data must be stored, preserved, refreshed, and copied onto new media, fuelling a material chain made up of server farms, electricity and the exploitation of mineral resources.

From the comparison between vegetal and digital memory emerge reflections on the ways we store data and preserve knowledge. «Plants operate with a decentralised structure: they have no brain, and their memory is distributed throughout the body, from roots to leaves. There is no central archive responsible for conserving information», explains Vetturi. «Plants seem to suggest decentralised, distributed, ecological and temporary forms of memory, in contrast with current digital models, which accumulate data permanently, centrally and often extractively».

When everything is preserved, as in the digital world, the very concept of forgetting disappears, and with it the possibility of renewing meaning. In the living world – and particularly in the vegetal realm – remembering and forgetting are complementary movements of a single vital process: retaining what is needed and letting go of what no longer serves.

«To imagine a digital architecture inspired by vegetal logics perhaps means accepting impermanence as a value rather than a loss», says Vetturi.

Every shift in accumulation implies a different perception of loss: holding on and releasing – in other words, remembering and forgetting – become part of the same gesture. In this sense, every memory is also an act of selection, a dynamic balance between permanence and dissolution.

Plants do not accumulate data linearly; they respond to the present by modulating traces of the past. Forgetting does not mean losing, but freeing space for new responses, new relations and new forms of adaptation.

This intuition goes beyond memory itself, transforming it into a symbolic principle that permeates everything. Faced with questions about data accumulation, ecological impact and the inequalities that arise from it, vegetal memory invites us to imagine another balance. Or rather, as Vetturi states: «It stands in counterpoint to the abyss of permanent digital registers. Perhaps this is the most radical advice: not everything needs to be archived; it is not necessary to accumulate endlessly. Memory can be a living space, in continuous transformation».

- Descartes, R. (1664). Traité de l’homme. Paris: Charles Angot. Si veda anche: Descartes, R. (1996). Œuvres complètes (C. Adam & P. Tannery, Éds.; Vol. 11). Paris: Vrin. ↩︎

- Bose, J. C. (1906). Plant response as a means of physiological investigation. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. See also: Bose, J. C. (1926). The nervous mechanism of plants. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. ↩︎

- Gagliano, M., Renton, M., Depczynski, M., & Mancuso, S. (2014). Experience teaches plants to learn faster and forget slower in environments where it matters. Oecologia, 175(1), 63–72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24390479/ ↩︎

- Wright, A. (2024). Worldwide IDC Global DataSphere forecast, 2024–2028: AI everywhere, but upsurge in data will take time (IDC Doc. No. US52076424). International Data Corporation (IDC). https://my.idc.com/research/viewtoc.jsp?containerId=US52076424 ↩︎