Born in the Bronx as a voice of redemption, rap has now entered educational workshops in Milan, offering young people an authentic space for expression. Lyrics reveal deep experiences, sometimes unconscious, which the art of rap manages to free and transform into dialogue. And in the age of Artificial Intelligence, a crucial question resurfaces: can an algorithm replicate the act of giving voice to oneself through music?

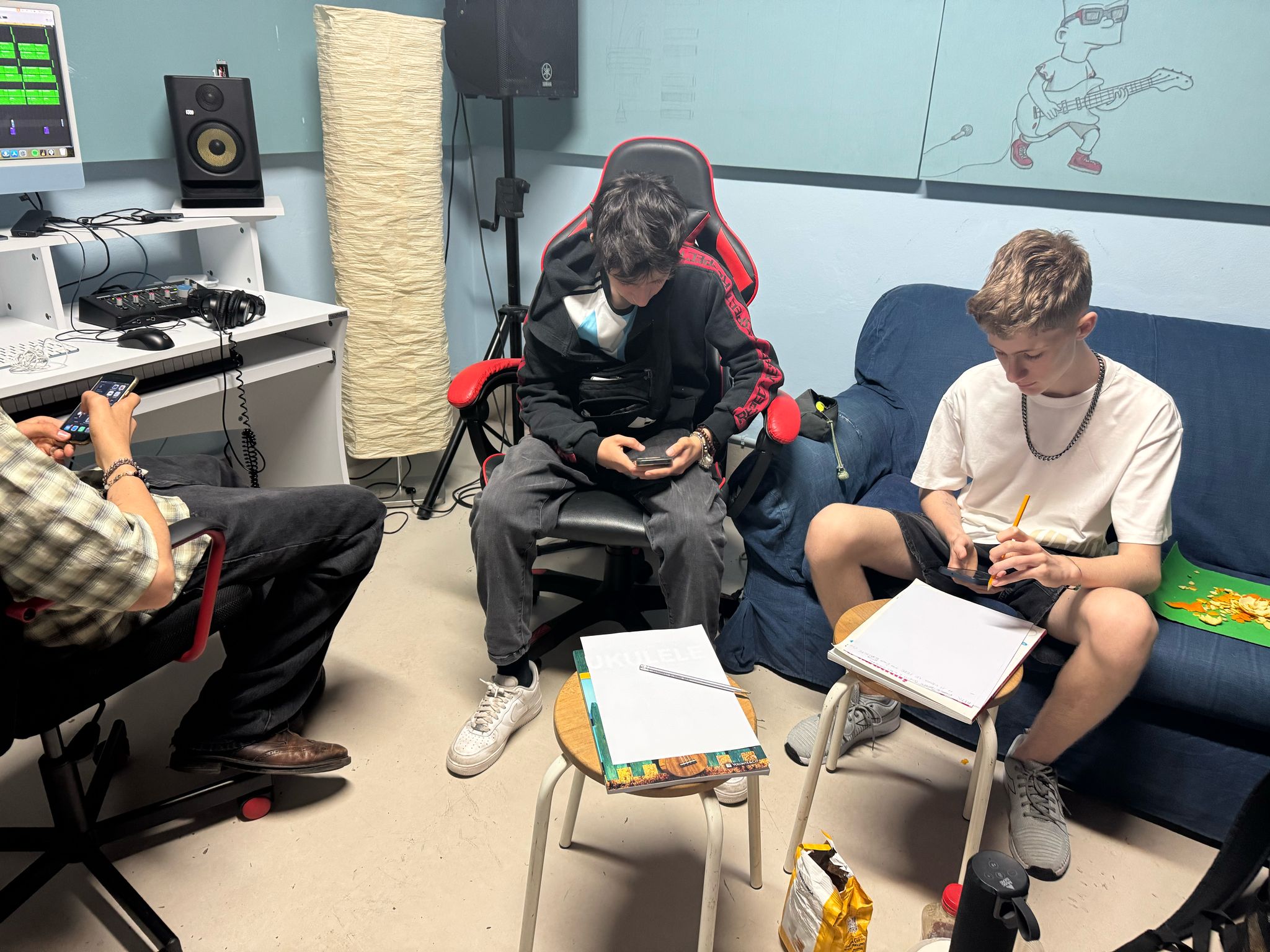

«Young people write a lot and in the most genuine way: they use their own language and allow parts of their lives or their way of reading reality to emerge, enriching those who listen too». This is what Mattia Lista, the educator who led a rap workshop in the Gorla-Turro area at the CAG Tempo per l’infanzia1, as part of the SpinOff project2, supported by the Lombardy Region Third Sector Call for Proposals, tells us. The purpose was shared: to counteract the educational poverty of citizens aged between 12 and 18 in Milan’s most peripheral and neglected areas. So was the method: to train and inspire creatively, through art and play, in order to broaden the cultural and experiential horizons of adolescents. A journey that demonstrates how rap can be a language to learn, practise and share. To be, and to feel, free.

At the origins of rap

«In today’s music scene, rap is certainly the most widely followed and understood artistic and narrative form in much of the Western world, especially among young people and very young people», explains Lista. «Every generation has its own culture, and this one has chosen rap».

Mattia Lista

Mattia Lista is a professional educator working for the cooperative “Tempo per l’infanzia”. Together with other educators and professionals in the sector, as well as friends, he founded the association 232 APS, which uses rap music to promote educational and musical workshops as a vehicle for social inclusion and free expression for adolescents attending communities, youth centres, schools or correctional institutions.

This genre was born in the Bronx in the 1970s and 1980s, in a context of urban and social neglect3: «completely apolitical, when in the early 1980s the dream of inclusion that had seemed possible in the 1970s had come to an end», says Lista, «everything and everyone had been abandoned to themselves, with unfinished works, schools and streets blocked. Even houses had lost value, and people were starting to set them on fire to collect compensation and move elsewhere. It is precisely in this context of decay that rap was born, as a game yes, but above all as a sense of revenge».

It is no coincidence that the term itself derives from Old English rap, “to hit, to strike”, soon also associated with “to talk quickly” or “to confess”. In African-American communities of the twentieth century, the word was transformed into “rhythmic speech”, eventually becoming identified with the musical beat4. Rap thus literally means “to speak in rhythm”: an intertwining of voice and verbal percussion that turns words into sound and storytelling into music.

It is not a cry of aggressive rebellion but rather a push towards integration. Its strength lies in its accessibility: it sets no barriers for those who wish to approach it and requires no sophisticated artistic skills.

«Rap is immediate», Lista explains, «unlike many other channels of expression such as poetry, which has formal rules, it has no rigid canon and does not require in-depth linguistic knowledge».

Why rap at school

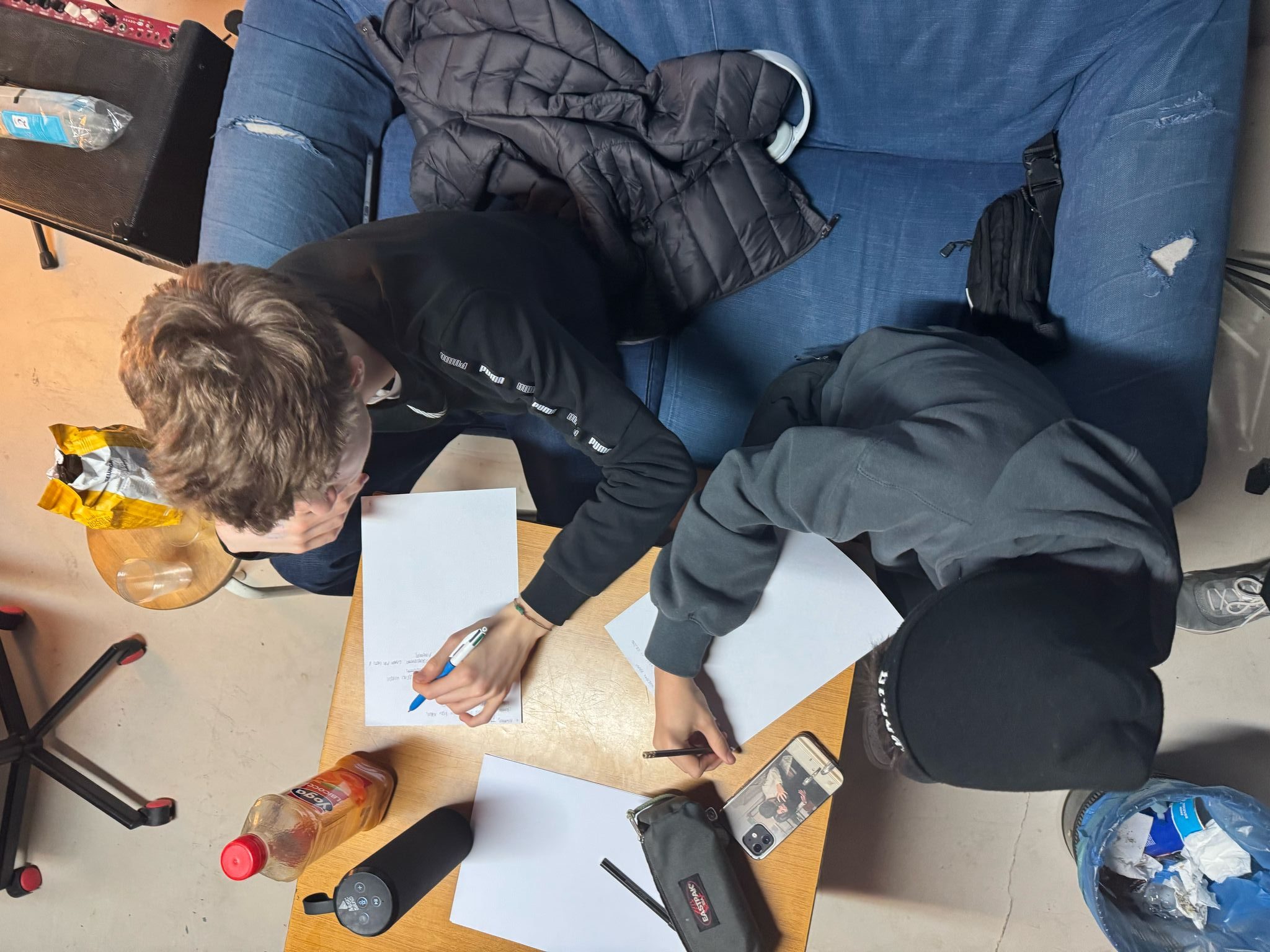

The workshop experience clearly showed rap’s power: to unravel thoughts, concepts and life experiences, allowing them to emerge spontaneously and authentically. At times unconsciously, but always without filters. After a brief technical introduction, participants in Lista’s workshop for SpinOff were able to write on their own, bound by only one rule: no offensive, sexist or racist lyrics. For the rest, absolute freedom. And that freedom was fully embraced: everyone took the non-rule literally, surprising even Lista himself, who has led dozens of rap workshops.

«We expected light rhymes, a few love verses, the “crush on the girl”, and instead deep themes emerged», recalls Laura Tanzi, project coordinator and founder of Lyra Teatro, pleased that the choice of rap proved successful.

Lyra Teatro

Lyra Teatro is a Milanese association founded in 2012 dedicated to contemporary dramaturgy, with original productions such as “Amorica” (2015), “Anti(Real)Gone” (2017) and Simon Stephens’ “Bluebird” (2023). From 2017 to 2025 it has been active at Fabbrica del Vapore as part of the project The Art Land, where it has produced its own shows and organised the “Fabbricanti di mondi” festivals, hosting independent companies from all over Italy. Alongside its theatrical activity, Lyra Teatro develops innovative social projects such as “La Fabbrica delle Culture”, using art as a tool for inclusion and to combat educational poverty in Milan’s suburbs.

Discover moreVisit the official website

It is no coincidence, observes Lista, that rap proves such a versatile tool: it works «both in contexts of inclusion – for foreigners and those with little knowledge of the language – and for young people with specific learning disorders, social or expressive difficulties».

An emblematic example is the transformation of «many Muslim girls, initially shy or sceptical, who later found a channel of expression, a free and safe space where they could write without fear of making mistakes».

But such an emotionally intense creative flow would remain sterile if it did not encounter someone willing to welcome it. This is where the educator comes in: to listen, recognise and gather those words, which make it possible «to access what many young people would not dare to say out loud». Lista, an educator by profession and by vocation, says that «lyrics reveal unexpected stereotypes and hidden vulnerabilities that then become opportunities for discussion on issues otherwise difficult to address and which would otherwise remain invisible». Music, in this sense, is a gateway for adolescents: «a channel that reveals unexplored and little-known experiences», comments Lista, «and at the same time provides a shared playground capable of strengthening trust».

However, what becomes evident in workshops does not find the same welcome in institutional settings. So says Laura Tanzi, who wanted to bring rap into her “Fabbrica delle Culture”, only to come up against mistrust and prejudice.

«In schools I encountered one main problem: rap was labelled as a miseducational activity and viewed with suspicion by both some teachers and many families», Tanzi explains.

«Even in cultural spaces that we thought would be more open and free of prejudice, attitudes of ostracism were not lacking. We were told: “Are there no more suitable activities for boys and girls? We do not want this space to be used for this”». According to Tanzi and her team, opponents missed the heart of the project: the workshop was not a fashionable youth exercise, but an artistic journey capable of translating individual experience into shared words, giving voice back to those who have none.

The rhyme no machine can generate

The arrival of Artificial Intelligence has raised new questions even in the field of creative expression, including in such free territory as rap. Lista does not demonise it: Large Language Model tools5can prove useful in other contexts, but they cannot replace personal writing when the aim is to give voice to oneself. «Rap is a channel to free what you have inside», Lista reflects. «You can write lyrics in any language, even in broken Italian, with few or many words, out of time or timeless, but it must be exactly what you want to tell me». AI can certainly help to find a rhyme or overcome a block, but it does not convey the personal imprint that makes each verse unrepeatable. «There is the risk of losing one of music’s greatest qualities: the authenticity of one’s own voice».

During the workshop, «someone tried to use it to overcome the difficulty of expressing a certain concept or to find a missing word», Lista recounts, but the experience showed that:

«Even young people who use AI for other purposes understand that without the direct act of writing, the game loses its meaning and it is no longer fun».

And fun remains a fundamental ingredient in the formula of rap, whether seen as an art form or used as an educational and developmental tool.

- Tempo per l’Infanzia and their activities https://www.tempoperlinfanzia.it ↩︎

- The SpinOff project www.progettospinoff.org ↩︎

- Rap from the Bronx to this day https://www.mescalina.it/musica/special/14/04/2023/speciale-hip-hop ↩︎

- Learn more about the origins of rap, Benvenga, L. (2022). Hip-hop, identity, and conflict: Practices and transformations of a metropolitan culture. Frontiers in Sociology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.993574 ↩︎

- A Large Language Model (LLM) is a type of Artificial Intelligence (AI) trained on vast amounts of textual data to understand, process, and generate human language effectively. ↩︎